Good advice 75 years on.

Good advice 75 years on.

When I happened upon what is said to be the last intact telegraph pole on PEI earlier this year, I searched the islandnewspapers.ca site for more PEI telegraph information and found the article reproduced below about the 1889 West Prince Forest Fire.

The information I’ve shared about the 1960 West Prince Fire is, by far, the part of my website that generates the most emails and comments, so I’ll add this article to the pile of Prince County fire info.

Note: I’ve left the term “squaw” in as it was commonly used at the time, but want to point out it is an archaic, offensive term for an Indigenous woman and best left in the past with similar racist, misogynistic language.

For some time past forest fires — many of them started for the purpose of clearing land — have been more or less prevalent in that portion of Western Prince County lying between Port Hill and Alberton. No consequences of a serious nature were anticipated from these fires, and the people generally paid but little attention to them.

However, the high wind of yesterday fanned the flames, and in an incredibly short time all that stretch of country between Conway Station and Alberton was a mass of fire. The flames spread with great rapidity, licking up almost everything in their way. The roaring of the fire as it spread was terrific. Everything possible was done to stay the progress of the flames, but without success. The fire fiend was master of the situation.

At O’Leary, Barclay’s mills were burned down. The dwelling house of Mr. White, the dwelling and office of Postmaster Frost and several unoccupied buildings met with a similar fate. It was only by the greatest exertions that the railway station house and coal shed were saved, clay having to be shovelled upon the fire to prevent its spreading in that direction.

It is feared that a squaw and her child, encamped a short distance behind the station at O’Leary, were burned to death. Rumors of other persons being burnt are also afloat, but lack confirmation. Let us hope that the rumors may prove groundless.

Between O’Leary and West Devon the fires were burning so close to the railway track that the express train, in charge of Conductor Kelly, had to be stopped several times to examine the track before proceeding.

At West Devon, Arthur’s mills were burnt down, and all his lamber was destroyed. The heat from the burning mills and lumber, as well as from the fires in the woods, burnt the sleepers and warped the rails for nearly half a mile, necessitating the stopping of the train at that place. Here Conductor Kelly took advantage of the only clear space available, and here for a time he and his men had to work hard to keep the train from being burnt up.

Besides Arthur’s mills, at West Devon, three or four dwelling houses were destroyed. It is said also that several farmhouses in the vicinity of that place succumbed to the devouring element, but we cannot vouch for the correctness of the report.

The heavy rain which began to fall between seven and eight o’clock last evening put the fires down a little and cooled the air considerably. This enabled the men to go to work and make the necessary temporary repairs to the track, in order that the train might be able to get over. By ten o’clock new sleepers and rails were put down and other work performed which enabled the train to pass over and proceed on her way.

The train had to proceed at a slow rate of speed. The sleepers in many places were burnt, and between Portage and Conway a culvert was destroyed. Here, again, the train had to stop, and temporary repairs had to be made before they could proceed. As they went along, the greatest care had to be taken to prevent an accident to the train. The line was carefully scrutinized to see that the rails and sleepers were in their places, and that the track was free from obstructions. On the way they could see the telegraph poles and trees, as they were attacked by the flames, sway to and fro finally falling — many of them across the track, necessitating further stoppages. At Portage Mr. Wallace’s dwelling house and saw mills were burned down. Several small houses between Portage and Conway also succumbed.

So great was the heat from the flames all along the route of the fire that it was with the greatest difficulty anything could be done to stay the progress of the flames. The smoke was also very troublesome. Some of the people living in the neighborhood took the first opportunity of sending their wives and families away from home, remaining behind themselves to battle with the enemy. But their efforts were largely futile.

Conductor Kelly’s train reached Summerside shortly before three o’clock this morning, where she remained until seven this morning, when she left for Charlottetown, arriving at half-past nine.

The mails and passengers by the St. Lawrence were brought to the city last evening by a special train from Summerside in charge of Station Agent Grady. As soon as the news of the delay in the arrival of the express was received here, Summerside was instructed to make up a special and forward the mails and passengers immediately on arrival of the steamer. This was done. The promptness on the part of the railway authorities is very commendable.

The western freight train, in charge of Conductor Ryan, was held at Port Hill by order of the Superintendent until daylight this morning, when she proceeded on her way. To-day all trains except the western freight above referred to are on time.

Up to the hour of going to press this afternoon there was no telegraphic communication west of Port Hill, so that no information as to the situation of affairs to-day is available.

The Daily Examiner, September 20, 1889

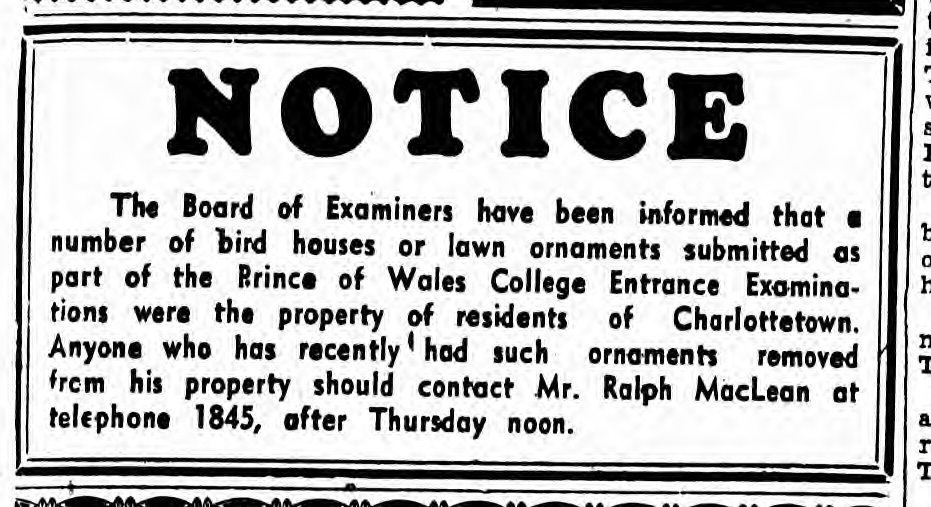

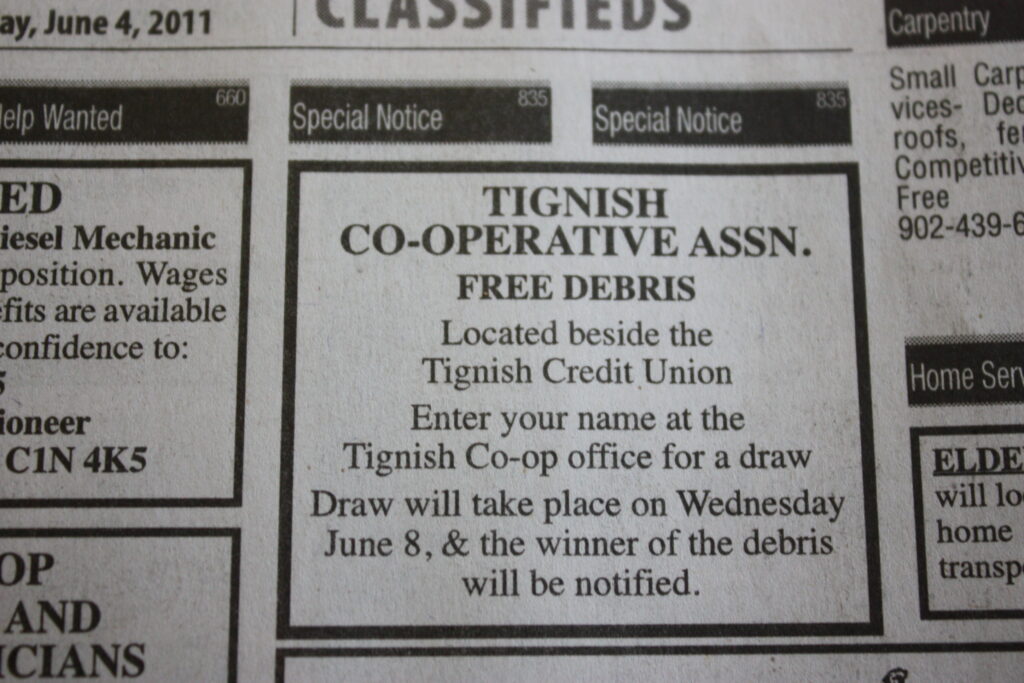

Classified newspaper ads of yore were often fairly stale and repetitive, but every so often one popped out. Here are a couple of my favourites.

And as an added bonus, feast your eyes on this unfortunate layout in a Lawton’s weekly sales flyer from November 12, 2011.

My great grandparents, Thomas and Agnes Phillips, lived on a farm on the Ellerslie Road. Agnes died in 1920 at age 66 and Thomas four years later, aged 72. Their youngest son, my grandfather Alvin, married my grandmother, Gladys, in 1912, and I assume they lived with Thomas and Agnes as Alvin eventually took ownership of the farm.

On September 30, 1925, all nine of Thomas and Agnes’ children returned to Ellerslie for a reunion. The rapidly growing clan would meet regularly over the following decades, into my lifetime. The last Phillips picnic I can remember was held at the West Point Lighthouse, 10 years or more ago.

My father knew most of his 38 Phillips first cousins quite well, though I could never keep them straight. Using a genealogy app (the reliable and powerful Reunion) for the past twenty years has definitely helped me with the “who’s yer father” game.

Those who met that September night are long gone, the last, Penzie (Martha Penrose “Penzie” Millar), in 1975. Their children are all gone now as well, the latest to die probably being my father’s brother, Sterling, in 2022, the youngest son of the youngest son.

FAMILY REUNION

On the evening of September 30th the family of the late Mr. and Mrs. Thomas H. Phillips of Ellerslie assembled together with their husbands and wives at the old home. The family were all present namely: Mrs. Joshua Millar and Mrs. E. S. Burleigh, Ellerslie, Mrs. Leslie MacLean, Arlington, Lot 14, Mrs. Russell MacArthur, Enmore, Willard of Summerside, Sanford, Sargent and Forrest of O’Leary and Alvin on the homestead. After partaking of goose and other delicacies all gathered in the living room where the evening was pleasantly spent in games, music and singing till after midnight when all joined heartily in singing “God Be With You Till We Meet Again” after which all departed for their homes, hoping to meet again on many such occasions in one unbroken family circle.

From the Charlottetown Guardian October 7, 1925, p6.

I’m happy to report that what is advertised as the last telegraph pole on Prince Edward Island does indeed still stand, insulators and all, on the Confederation Trail halfway between Elmsdale and Alberton, and it’s also easily visible from the Dock Road. The day I found out about the pole’s improbable existence, on a walk from Elmsdale towards Alberton, we had stopped just about halfway between the two communities at the beginning of a bend in the trail.

As we moved towards our previous-day’s stopping point, this time from Alberton, a couple of days later, I began to doubt we would find it still standing. Suddenly there it was, a few feet around a bend from where we had stopped and turned back.

The PEI Railway opened in 1875, 150 years ago this year, 50 years after the first recorded passenger trail journey between Stockton and Darlington on September 27, 1825 (a gorgeous episode of the BBC Radio 4 Illuminated documentary series brings that event to life). Could this pole be 150 years old? If so, it has survived forest fires and ice storms, vandals and woodpeckers and rot. I suspect its survival might be due to the fact it is planted in a swampy area, replete with spiky bushes, at the bottom of a steep bank. “Let’s just leave ‘er, boys!”

As historic sites go, it’s not Green Gables, but it is a relic of an important Island story. The railway opened up commerce and travel to people in far-flung parts of PEI, and allowed farmers and fishers access to more markets. Building the railway nearly bankrupted our small island colony, so PEI finally agreed to join Canada in 1873 so the project could be finished with an influx of federal dollars.

In addition to signalling train travel, the telegraph that accompanied the railway brought news and could summon assistance in case of emergency. Imagine living in non-electrified 19th century Alberton, heating and cooking with wood, lighting with candles or newly-discovered kerosene, travelling by horse and wagon or sleigh, and then suddenly being able to send a telegram to your brother in Boston asking about work opportunities or ordering supplies from Holman’s in Summerside in the morning and then having them shipped to you by train that very afternoon? It would have felt like magic. And that pole helped make all that happen.

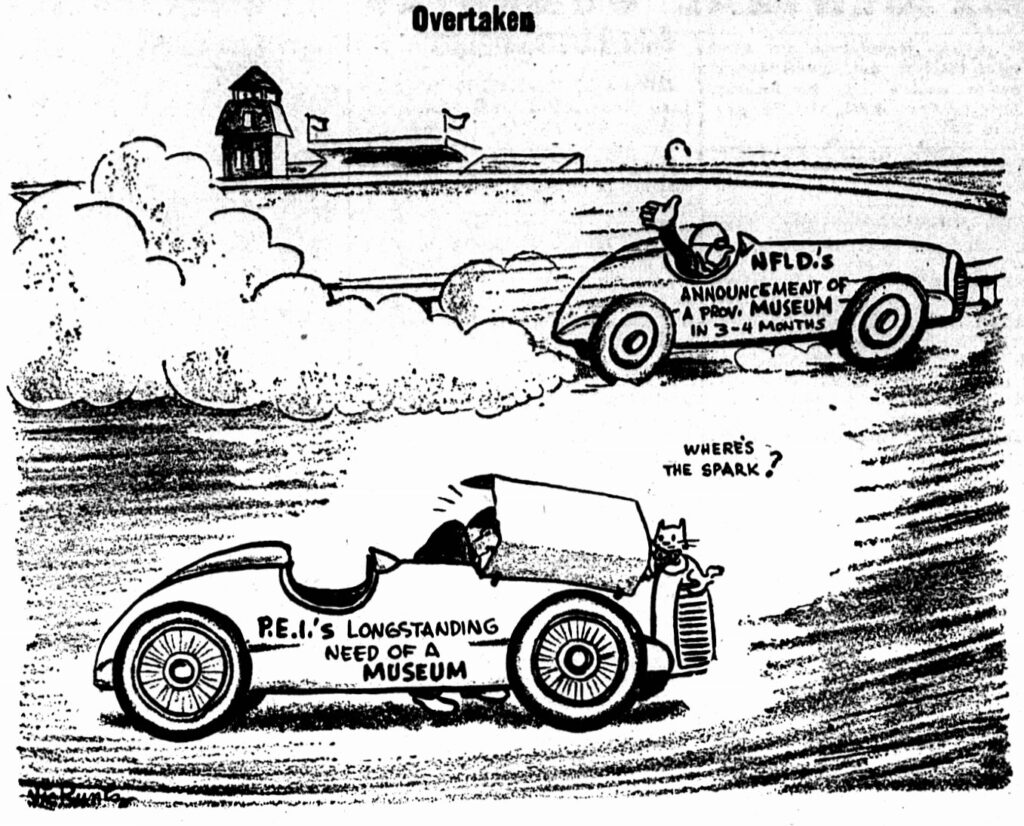

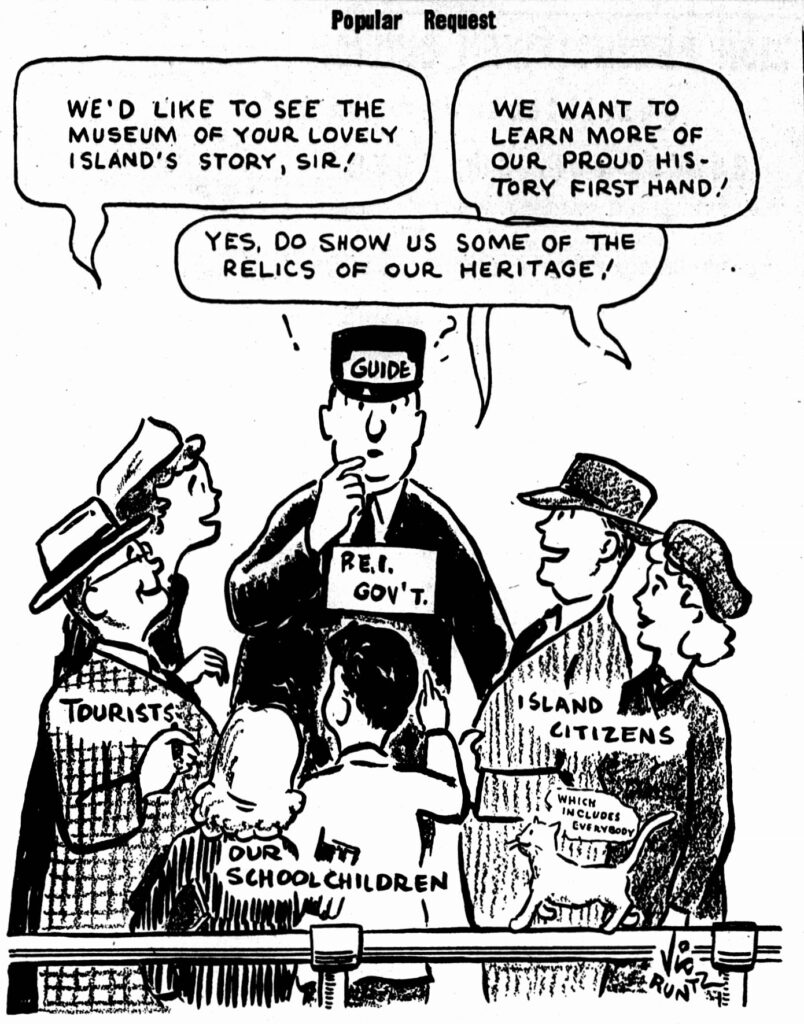

As much as it was a thrill to find the pole right there in the open, I wonder if someday it might be able to stand proud and straight inside a centrally-located provincial museum? Time will tell.

Steven and I walked the Confederation Trail from Elmsdale corner half way to Alberton and back this morning, about six kilometres round trip. We had planned to walk to Alberton and back, but the cold wind was whipping and that was far enough.

We saw a couple of lupins blooming well out of season, some daisies, lots of apples and even some grapes. As always, the trail is beautifully maintained and clean. Benches and shelters with picnic tables along the way make this entire trail an ambler’s dream.

Interpretative storyboards have added interest to each walk we’ve taken, but this one really caught my attention: the last telegraph pole on PEI? Yes please!

LAST POLE STANDING

The P.E.I. Railway was welcomed by communities across the province that had previously been limited to travel only via poor (often impossible) roads and coastal boats. In May 1875 people who had known isolation all their lives were suddenly able to reach any of the Island centres with comparative ease. They received mail twice a day rather than twice a week. What a change! The railway also connected rural communities with the world. The Island had an underwater telegraph cable to the mainland since 1851, but the service was only available in large urban centres. Telegraph lines now followed the tracks from Tignish to Souris, linking all railway stations. It was used for emergencies along the line but also by government and business. The entire service was operated by Canadian National Telegraph from the 1920s but previous operators included the P.E.I. Railway and Anglo-American Telegraph. The last pole standing is located about halfway between Alberton and Elmsdale.

We were halfway between Alberton and Elmsdale! I looked near the sign for a pole to match the photo, but no luck. I’m now anxious to make the trek from Alberton to where we stopped to see if that last pole complete with insulators still stands.

I did notice a couple of poles without insulators on our return walk that looked like the pole on the sign. They were shorter than most poles, and three notches were clearly visible at the top of both. They seem to be holding fibre op cable, the modern telegraph, I suppose.

In trying to (unsuccessfully)* find out what the little wooden insulator holders are called, I came across some wonderful websites, including one for the UK-based The Telegraph Pole Appreciation Society and, well, anything I clicked on after searching for “parts of Canadian telegraph poles”.

*I did some further reading and believe those little wooden pieces that held the insulators may have been called side-block brackets, as per this archived article by John Gilhen**, “Telephone and Telegraph Insulators: The End of an Era”, published in 1976 by the Nova Scotia Museum.

**John Gilhen died in April of this year. He had a 50 year career at the Nova Scotia Museum in the natural history section. His obituary noted he was “an avid collector including antique glass and insulators, hockey pins and cards.” He sounded like a marvellous, interesting person.

Peter’s wonderful post about Charlottetown’s venerable Bookmark (his photos of tiny details around the shop and their aerie office are delightful) made me dash pre-morning-coffee to rifle through my small bookmark collection to confirm his observation that there has never been a “the” before the bookstore’s name. Me too, Peter, me too.

I guess I had my final visit to the Queen Street location this past Wednesday, when I dashed in to pick up a book order while a friend waited in my illegally-parked car. I didn’t know to give a final nod to the place where I’ve spent many happy hours, so Peter’s post allowed me one last wistful glimpse. Looking forward to the new digs!

Late summer 1925 was filled with federal election rumours, and Canadian Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King eventually did call a general election for October 29 of that year. King had some housekeeping to do before the election, and one of his tasks was filling half of PEI’s seats in the Senate, which meant appointing two new senators to replace John Yeo and Patrick Murphy, who had both died during the previous year.

The August 31, 1925 Charlottetown Guardian editorial page was full of Senate news and opinion:

Then, breaking front page news from the September 3, 1925 Guardian:

Senators Who May Or May Not Be

Rumors were rife in the city yesterday regarding appointments to the vacant senatorships, to the effect that the choice had fallen upon Mr. J. J. Hughes, M. P., and Mr. Creelman McArthur, Summerside. No confirmation of this rumor was available last night but no doubt official announcement will be forthcoming very shortly. The Liberal decks are being cleared for action and no doubt all possible appointments will be made before the Liberal conventions are held as some possibilities for a senatorship may be willing to accept nomination as second choice, if they should fail in bagging the bigger plum. Mr. Nelson Rattenbury who has been a senatorial possibility till the last minute has been eliminated from the list by a consolation prize of a seat on the C. N. R. Board of Directors. What consolation will be handed out to the remaining aspirants has not yet been divulged, but anything is possible now that appointments will be handed out promiscuously in view of the pending election. In the meantime until more definite information is to hand, Messrs J. J. Hughes and Creelman McArthur will enjoy the felicity of being senators pro tem but subject to revision.

I can confirm that the rumours about Hughes and M(a)cArthur were true, and Creel resigned his seat in the PEI Legislature on September 5. Now to fire up the time machine and go back to place a few bets!

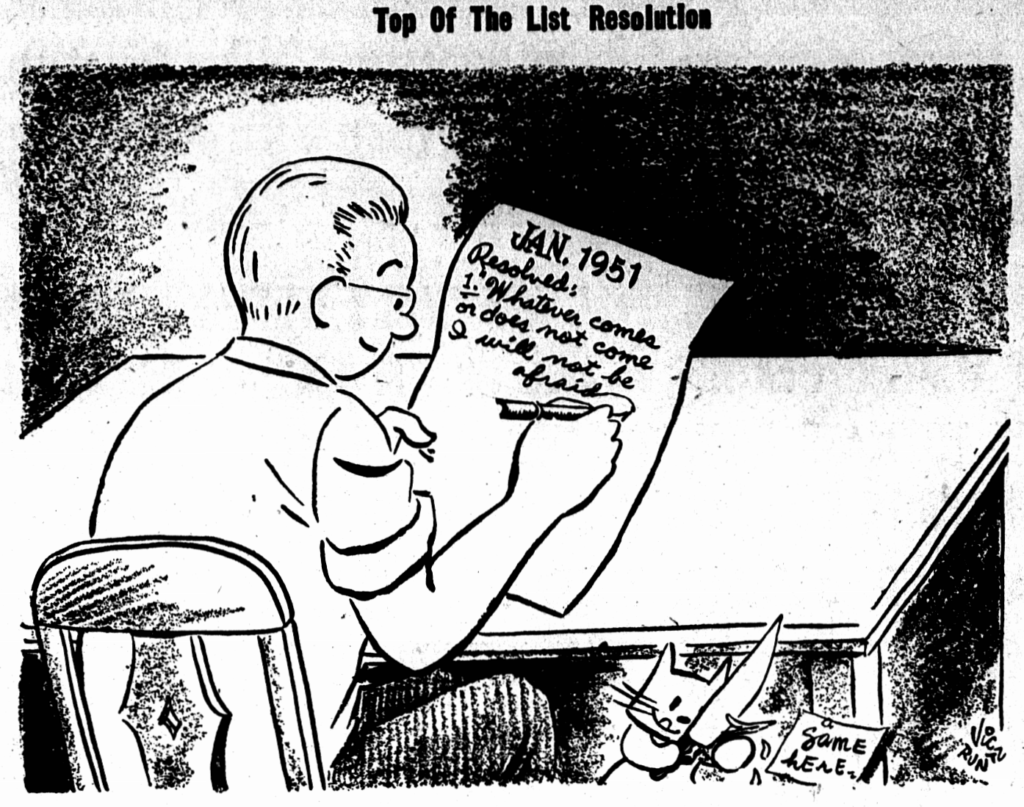

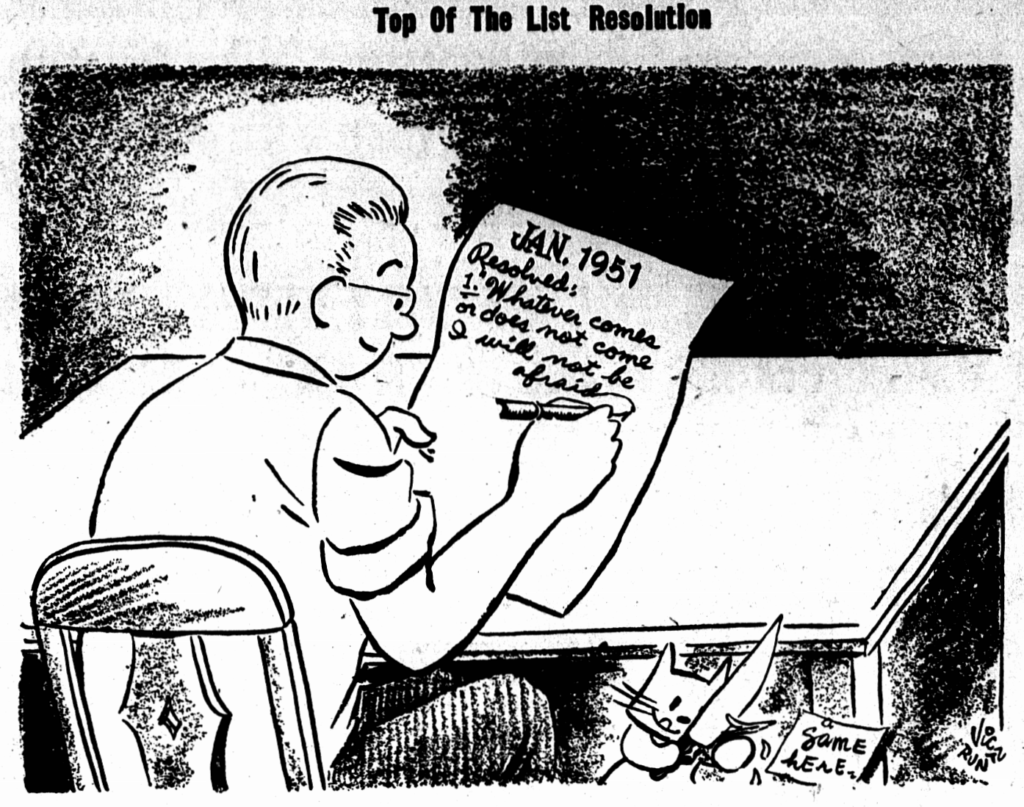

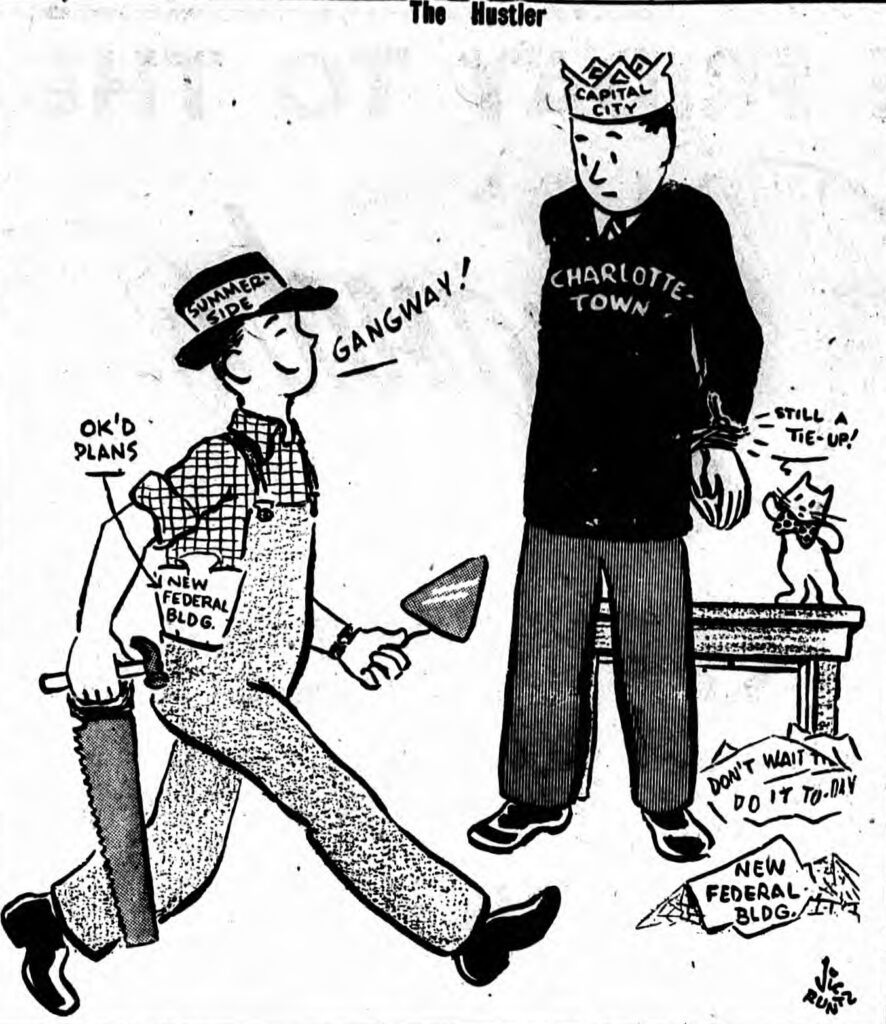

Here are some 75-year-old Vic Runtz cartoons from the Charlottetown Guardian I’ve enjoyed over the past few months. Plus ça change…

This tragic item on the front page of the May 19, 1925 Charlottetown Guardian left me wanting to know more about Roma Theresa Morgan. I’ve pieced together a bit of a history from a couple of census records and a baptism record for Theresa or Teresa, born May 10, 1894 probably near Fort Augustus, PEI, where she was baptized on May 27, 1894 at St. Patrick’s church, to John Morgan (born in Ireland around 1839) and Mary (Monaghan) Morgan (born Ireland August 10, 1854).

By the 1911 Census, John was dead and Mary and Theresa were living with a border at 58 Queen Street, Charlottetown. By 1931, Mary was living with her oldest child, Joseph, who was single and a farmer in Watervale, PEI.

Dear Theresa would have just turned 29 around the time of her death in faraway Brooklyn. How did a PEI girl get to New York 100 years ago and become a magazine cover model? Did Theresa send money back to her family, along with copies of the magazine covers? What must they have thought of her new life?

Charlottetown Girl Takes Poison by Mistake

(Special to the Guardian) NEW YORK, May 18 - Three years ago pretty Roma Theresa Morgan, whose mother and sister live at 58 Queen Street, Charlottetown, P. E. I., came to New York, to win fame and fortune. Today she is on her way back home in a casket, the victim of poison taken by accident.

Roma posed for several of the greatest magazine cover artists in America but a few months ago was obliged to cease working because of poor health. The other evening her landlady Mrs. Elsie Ilse, who maintained a furnished rooming house over in Brooklyn found the girl writhing on the floor of her room. She was rushed to a hospital but all efforts to save her life were in vain. The police say the girl mistook a bottle of poison for rheumatism medicine.

No notes were found which would indicate suicide and other roomers in the house knew her as a cheerful friendly person.