Good advice 75 years on.

Good advice 75 years on.

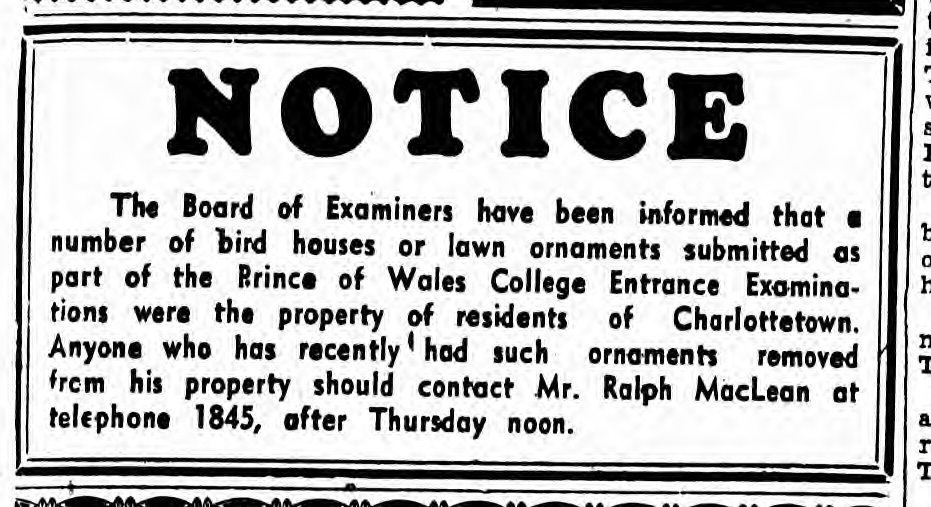

Classified newspaper ads of yore were often fairly stale and repetitive, but every so often one popped out. Here are a couple of my favourites.

And as an added bonus, feast your eyes on this unfortunate layout in a Lawton’s weekly sales flyer from November 12, 2011.

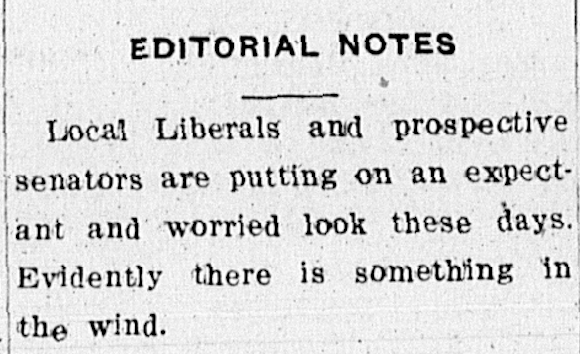

Late summer 1925 was filled with federal election rumours, and Canadian Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King eventually did call a general election for October 29 of that year. King had some housekeeping to do before the election, and one of his tasks was filling half of PEI’s seats in the Senate, which meant appointing two new senators to replace John Yeo and Patrick Murphy, who had both died during the previous year.

The August 31, 1925 Charlottetown Guardian editorial page was full of Senate news and opinion:

Then, breaking front page news from the September 3, 1925 Guardian:

Senators Who May Or May Not Be

Rumors were rife in the city yesterday regarding appointments to the vacant senatorships, to the effect that the choice had fallen upon Mr. J. J. Hughes, M. P., and Mr. Creelman McArthur, Summerside. No confirmation of this rumor was available last night but no doubt official announcement will be forthcoming very shortly. The Liberal decks are being cleared for action and no doubt all possible appointments will be made before the Liberal conventions are held as some possibilities for a senatorship may be willing to accept nomination as second choice, if they should fail in bagging the bigger plum. Mr. Nelson Rattenbury who has been a senatorial possibility till the last minute has been eliminated from the list by a consolation prize of a seat on the C. N. R. Board of Directors. What consolation will be handed out to the remaining aspirants has not yet been divulged, but anything is possible now that appointments will be handed out promiscuously in view of the pending election. In the meantime until more definite information is to hand, Messrs J. J. Hughes and Creelman McArthur will enjoy the felicity of being senators pro tem but subject to revision.

I can confirm that the rumours about Hughes and M(a)cArthur were true, and Creel resigned his seat in the PEI Legislature on September 5. Now to fire up the time machine and go back to place a few bets!

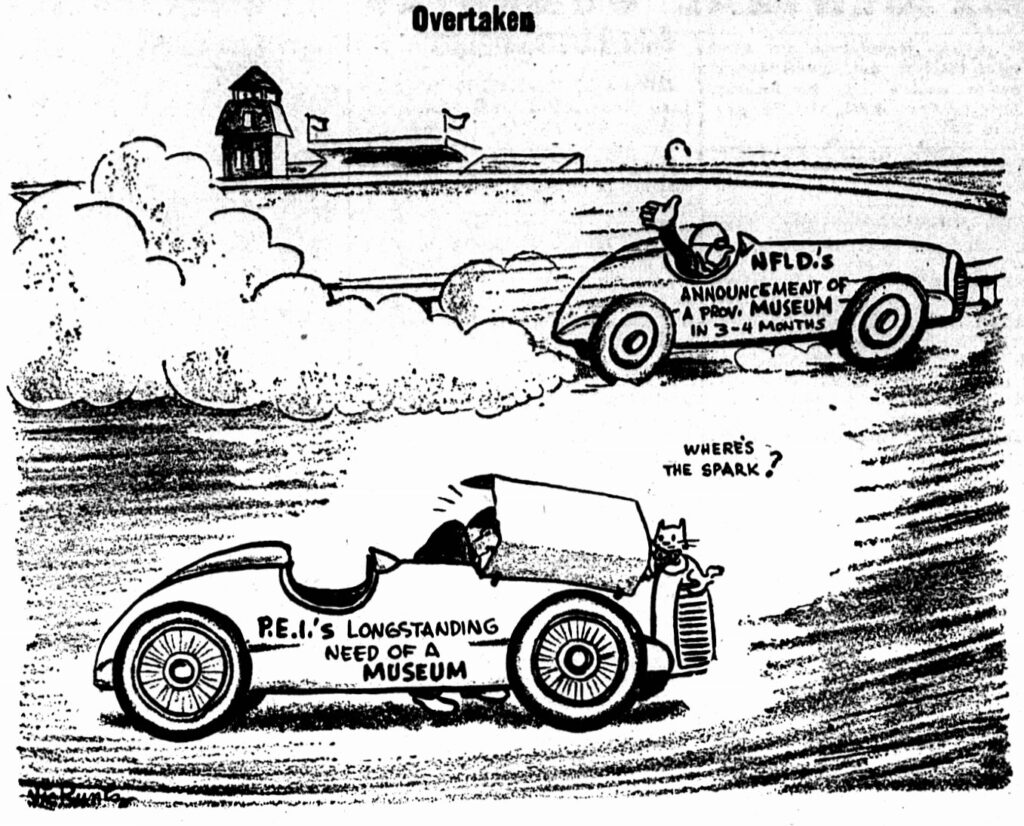

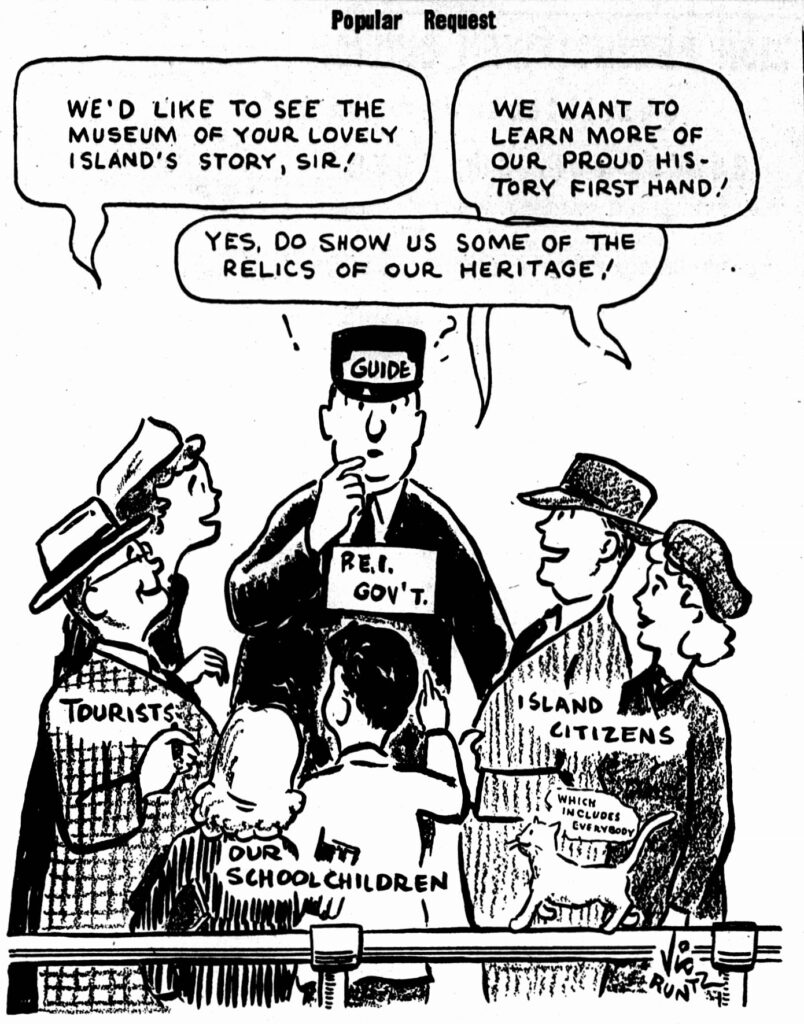

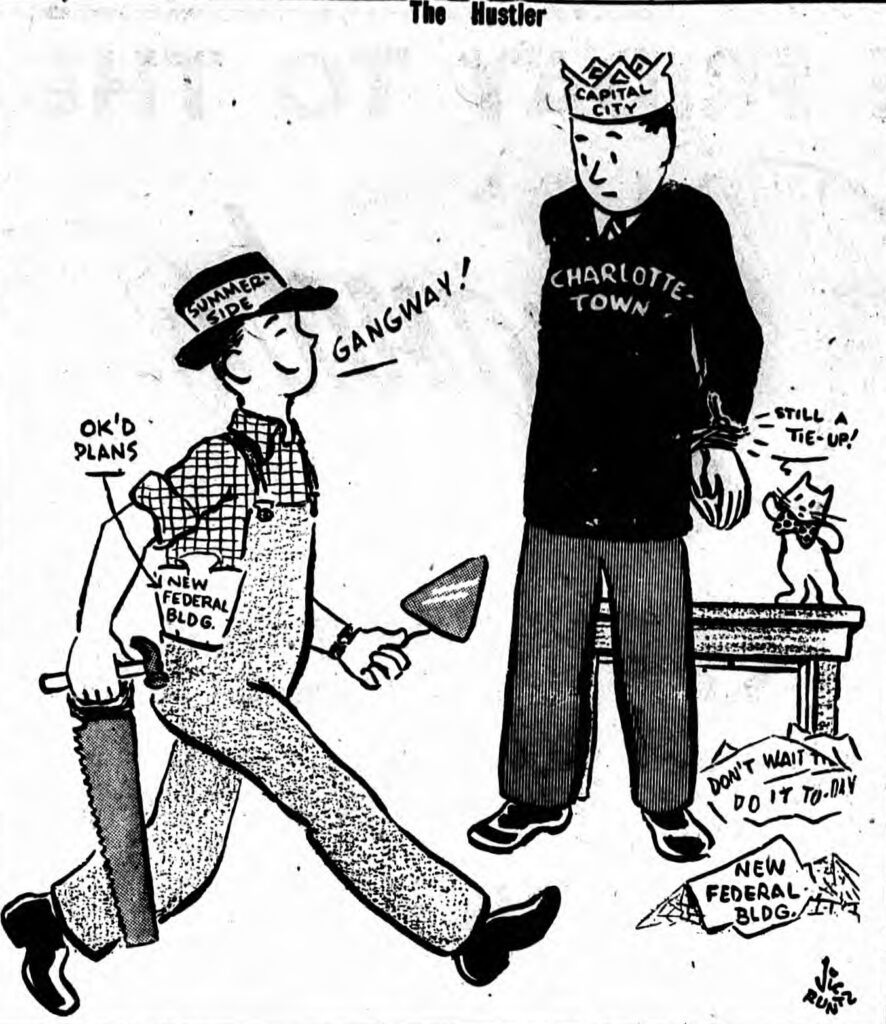

Here are some 75-year-old Vic Runtz cartoons from the Charlottetown Guardian I’ve enjoyed over the past few months. Plus ça change…

This tragic item on the front page of the May 19, 1925 Charlottetown Guardian left me wanting to know more about Roma Theresa Morgan. I’ve pieced together a bit of a history from a couple of census records and a baptism record for Theresa or Teresa, born May 10, 1894 probably near Fort Augustus, PEI, where she was baptized on May 27, 1894 at St. Patrick’s church, to John Morgan (born in Ireland around 1839) and Mary (Monaghan) Morgan (born Ireland August 10, 1854).

By the 1911 Census, John was dead and Mary and Theresa were living with a border at 58 Queen Street, Charlottetown. By 1931, Mary was living with her oldest child, Joseph, who was single and a farmer in Watervale, PEI.

Dear Theresa would have just turned 29 around the time of her death in faraway Brooklyn. How did a PEI girl get to New York 100 years ago and become a magazine cover model? Did Theresa send money back to her family, along with copies of the magazine covers? What must they have thought of her new life?

Charlottetown Girl Takes Poison by Mistake

(Special to the Guardian) NEW YORK, May 18 - Three years ago pretty Roma Theresa Morgan, whose mother and sister live at 58 Queen Street, Charlottetown, P. E. I., came to New York, to win fame and fortune. Today she is on her way back home in a casket, the victim of poison taken by accident.

Roma posed for several of the greatest magazine cover artists in America but a few months ago was obliged to cease working because of poor health. The other evening her landlady Mrs. Elsie Ilse, who maintained a furnished rooming house over in Brooklyn found the girl writhing on the floor of her room. She was rushed to a hospital but all efforts to save her life were in vain. The police say the girl mistook a bottle of poison for rheumatism medicine.

No notes were found which would indicate suicide and other roomers in the house knew her as a cheerful friendly person.

These were the front two pages of The Guardian newspaper yesterday. It wasn’t a wrapper, as I first assumed, as the back two pages had normal newspaper articles.

The next page also looked like a front page, but the reverse of this page was numbered 4, so it was the third page.

Yes, the front two pages were labelled in small print as paid political advertising, but who paid the bill, and how much did it cost? It’s difficult to take this any other way than a huge endorsement of one federal party over the other. Postmedia could have refused to take the ad, or agreed only to place it further back in the paper. This was a choice. And I’d be as disappointed if it were an ad for the Liberals or any other party.

Deceptive, creepy and mercenary.

Freeland made the front page of the Charlottetown Guardian on this date in 1949 with the sad news that the body of Augustine “Gus” Gain had been found in the woods.

The body of Augustine Gain, 81, was found about ten o’clock on the morning of December 24th in the woods about a mile from his home. He had been missing since the previous day and an all-night search had been carried on.

An investigation was conducted by members of Summerside Detachment R.C.M.P., and the Coroner, Dr. Austine Delaney and it was decided that death was due to natural causes and exposure and that an inquest would not be necessary. The body was frozen when found.

A considerable sum of money was found in various pockets of the clothing. The elderly man had lived alone for a number of years and was last seen alive about noon the day previous when he left the store of A. Philips after procuring supplies and started for his home a mile and a half away.

The day was warm and the walking was heavy. That evening it was noticed by his nephew, James Gain, who lives nearby that there was no light in his uncle’s house and on investigation he found that he was missing. – S

I asked my mother if she remembered someone called Augustine Gain and she said, “Oh yes, Gus Gain. He used to come to our store.” Clinton Morrison’s history of Lot 11, Along the North Shore, says Gus lived in the community of Murray Road, so I asked my mother where Gain’s house was and she replied, “There by the water, you know, by Gain’s Creek.” Of course. There are no more Murrays or Gains in our area, but their names live on.

So there is a typo in the article, as the store mentioned in the article did not belong to A. Philips, but to my father H. Phillips, or rather, H.E. Phillips. Harold Edmund. He used both initials in business, and I have no idea why, except that it probably made him sound more prominent when in fact, in 1949, they were barely scraping by.

It was probably my mother who served Gus that Thursday two days before Christmas, and she could have been the last person to see him alive. The drive from our old store to where Gus lived is only about five minutes by car, but that’s a round about route if you are on foot, so he would have walked a well-worn path through the forest as a short cut. We sometimes used that same path for snowmobiling when I was a child in the 1970s, and I can still pick it out when I look at recent aerial photos. It’s swampy in places back there, would be terrible walking if the ground wasn’t completely frozen.

This blog now memorializes two PEI men named Gus who died in 1949.

I had always assumed the abdication crisis of 1936 was first set in motion when the Prince of Wales, later Edward VIII, met Wallis Simpson in 1931, but it seems David Windsor might have been finding the prospect of leading the British Empire too daunting a task as far back as 1924, if this gossipy bit from the November 6, 1924 Charlottetown Guardian is any indication.

Silly Rumor About Prince of Wales

LONDON, Nov. 6.- The Prince of Wales may possibly renounce his right to the throne of England. This rumor kept the Prince eager company during his trip from America on the liner Olympic last week and greeted him as it was whispered through the crowds when he arrived at Southampton, home again after his vacation.

This rumor set the whole boat buzzing before the voyage was half way done. The Prince himself scoffed at it. But one of his aides went to the trouble of issuing official denial.

Perhaps the circulation of the rumor was one reason for the extraordinary censorship on the Olympic. As soon as it was discovered that there were several newspapermen on board, orders were issued that every message must be ok’d both by the purser and Captain Lascelles, the Prince’s secretary. Very few messages passed this board of censorship, and any that did were limited to twenty words. During the voyage the prince danced chiefly with Mrs. H. P. Peabody of New York, and Miss Esme Magann, of Toronto, whom he met in Canada and who made the trip with her mother, Mrs. Plunkett Magann.

And who could blame him for wanting out? He’d had a lovely visit to North America, being feted and paraded everywhere he went. He visited his Alberta ranch to play cowboy for a bit, and generally seemed to have a “Wales” of a time golfing and dancing and looking dapper and rich. Why spoil all that fun with the boring ceremonial grind of being a constitutional monarch?

Cyrus Ching, a renowned labour mediator in the United States, was born in Prince Edward Island, but I hadn’t heard of him before reading about him in the October 26, 1949 edition of the Charlottetown Guardian.

I am familiar with his dry wit, though, and I wonder if it came from his early PEI childhood, which sounded quite challenging. I’ve known a few farmers possessed of a dry wit, usually accompanied by the calm and goodnatured mien necessary to persevere in an occupation where you are constantly at the mercy of weather and fortune. I have benefited from being on a couple of community boards with some intelligent, dry-witted farmers, and have learned a lot from them about curbing my chatterbox tendencies and making few, brief comments after all the other chatterboxes have exhausted themselves. It is a powerful technique, and people listen.

Here’s the entire article (including, unfortunately, a bit of the casual racism of the time):

Washington D.C., Oct. 25 – One of the few reassuring sights in strike-tense Washington these days is a massive man with a shy grin and a huge pipe who lumbers in and out of the White House, the least mysterious participant to enter mysterious meetings.

If you were to point him out to a stranger and say, “That’s the man who is in the middle of one of the most crucial strikes in U.S. history,” the stranger wouldn’t believe you. Cyrus P. Ching, Director of the Federal Mediation and Conciliation Service, just doesn’t look like the “crucial” type.

Only clue to the tremendous responsibility which he has carried around for the last couple of years in the job, and which today is at peak-load, is a slight stooping of his huge frame and a minor hesitation in his step. Even stooped shoulders, however, don’t bring his six-foot, seven-inch frame down to the level of average men.

Few persons have the privilege of becoming legendary while they are still alive. Ching has that honor. There just seems to be a sort of legendary quality about the constant, semi-amused, yet quietly profound manner of the man.

Many Anecdotes

There’s almost no limit to the anecdotes involving his dry humor and the subtle devices he has used to get labor and management in a friendly mood. He calls these things “establishing better communications with people.”

Once he was having a particularly difficult time with a union man named Lee, during a tough negotiation. Lee was about to walk out when Ching said: “Maybe we’d better get out of this labor business altogether and start a little laundry.” After the moment it took for all present to catch the gag, there was a big guffaw which relaxed the tension and greased the way for a successful settlement. His favorite line to use on a negotiator who has his dander up is to ask him if he ever heard of “rule six” of the British Navy. That brings the question of what rule six is, and then Ching tells this story:

“During World War I U.S. Navy Secretary Josephus Daniels was visiting British Admiral Beatty. In their presence a captain started sounding off about how the war was being run. Beatty said to him in a sharp voice. ‘You are violating rule six of the British Navy.’ That shut him up and later Daniels asked Beatty what rule six was. Beatty replied, ‘Never take your self too damn seriously.'”

Nation’s Foremost Mediator

Ching is the nation’s No. 1 labor mediator for many more reasons than having a good collection of stories. He has had a key part in the most controversial piece of labor legislation in history, the Taft-Hartley Act, and after two years still has the confidence and friendship of both labor and management leaders.

Ching sums up his philosophy on labor relations in this way:

“Promoting proper labor relationships is nothing you can do overnight. It isn’t anything you can do by law. You can set up machinery to soften the blows of people not inclined to get along together. You can pad their gloves a little, and it may be necessary to have a referee to do that. But in the last analysis labor relations begin down in the bottom department of the plant between the foreman and employee.”

On his job as boss of the Conciliation Service he says:

“We cannot measure the efficiency of a conciliation service by the number of fires it extinguishes. We can measure it only by the machinery we build up to encourage people to settle their own disputes. In other words, the test of conciliation is how few disputes lead to strikes and how many disputes are settled directly by the parties, with whatever help we can supply. My job is to contribute to fire prevention.”

Born In P.E.I.

Ching knows the hard road of success. At 13 he took over management of the Prince Edward Island, Canada, farm on which he was born. After a stint of fur trading and commercial fishing following his farming, he went to a Canadian business school. Soon after graduation at 19, he took off for the big city of Boston. It has been written:

“All he had at the time, when he stepped off the train, was a gripsack, a copy of Bryce’s “The American Commonwealth,” which he had read at 14, and $31.”

First job was on the Boston Elevated Railway Co. Not too many years later he was assistant to the traction company’s president. He had studied law by that time and personnel matters were his specialty. Then labor relations became his sole endeavor and he wound up director of that activity for the U.S. Rubber, just before he came to Uncle Sam.

When people ask him about his Chinese-sounding name – which is Welsh – he replies: “I am three-quarters Scotch and one-quarter soda.”

The article notes that Cyrus had “a slight stooping of his huge frame and a minor hesitation in his step,” but the writer neglected to mention that Cyrus was 73 years old in 1949! According to his Wikpedia entry, he worked up until his death in 1967 at age 91. His Wikipedia entry links to a National Archives clip of Cyrus on an early US television program, and it’s worth a look to try to hear his Island roots in his speech.

People from Trois–Rivières/Three Rivers, Quebec are known as Trifluviens/Trifluvians.

People from the recently-created municipality of Three Rivers, Prince Edward Island, are known as residents of Three Rivers.

I don’t think any of the three rivers (Cardigan, Brudenell and Montague) that make up Three Rivers count as fleuves rather than rivières, but it sure would be fun to add Trifluvians to our Island lingo. Let’s do it!

(I came to all this through a 1964 article about Quebec singer Pauline Julien declining an invitation to perform for Queen Elizabeth II during her visit to PEI in October 1964 to mark the centenary of the Charlottetown Conference. Julien’s Wikipedia entry notes she was born in Trois–Rivières and was “the companion of the poet and Québec provincial MLA Gérald Godin, another Trifluvian and sovereignist.” Julien and Godin were both arrested and held for eight days during the 1970 October Crisis, then released without charge. I don’t know if her refusal to sing for QEII had anything to do with her arrest under the War Measures Act, but I doubt it helped.)