I can’t easily identify my favourite band or book or movie. I could give you a top ten list of favourites, but would not be able to single out just one.

My favourite podcast of all time is easy, though: A History of the World in 100 Objects from BBC Radio 4 in collaboration with the British Museum. It was broadcast in 2010 and I downloaded every podcast episode over our 1.5 Mbps internet connection and listened while I worked outside that fall.

The idea of looking at the span of human history through 100 objects captivated me, and I started my own 100 Objects project on an earlier version of this blog, planning to write about a different object once a week. I wrote about a couple of things from my unorganized collection of stuff, but didn’t continue both because of time constraints and not being certain of what I wanted to say or even why I thought something needed to be said!

I’m going to start again, this time documenting things that will tell the story of my family, my community and me, but only when and as the spirit moves me.

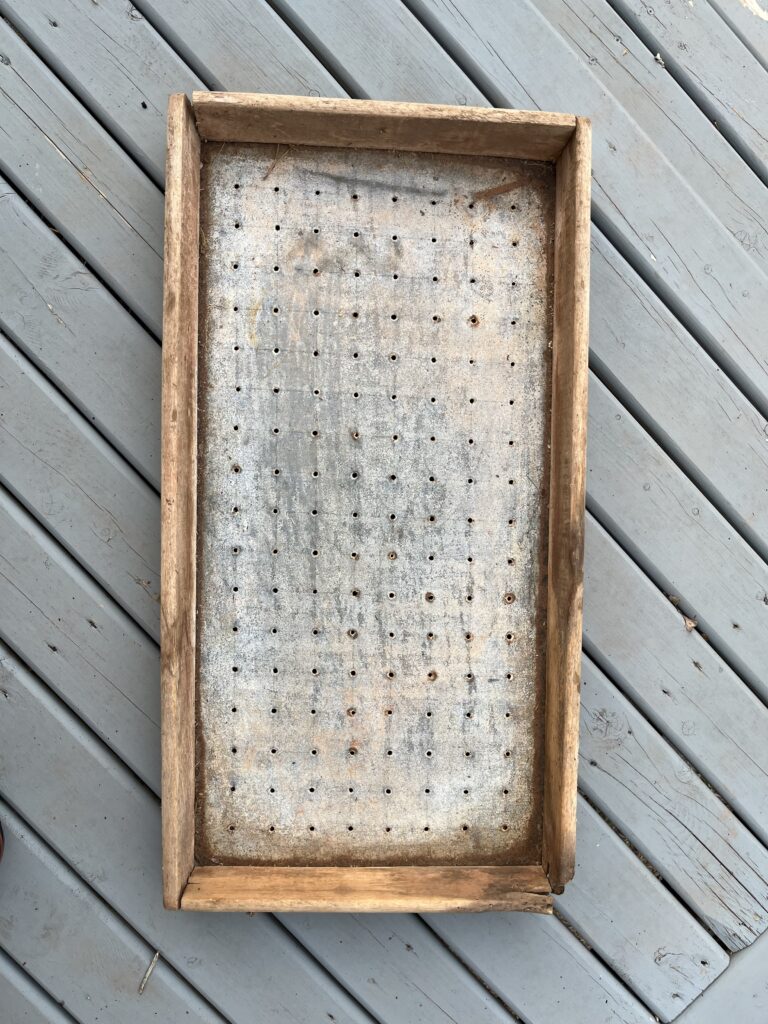

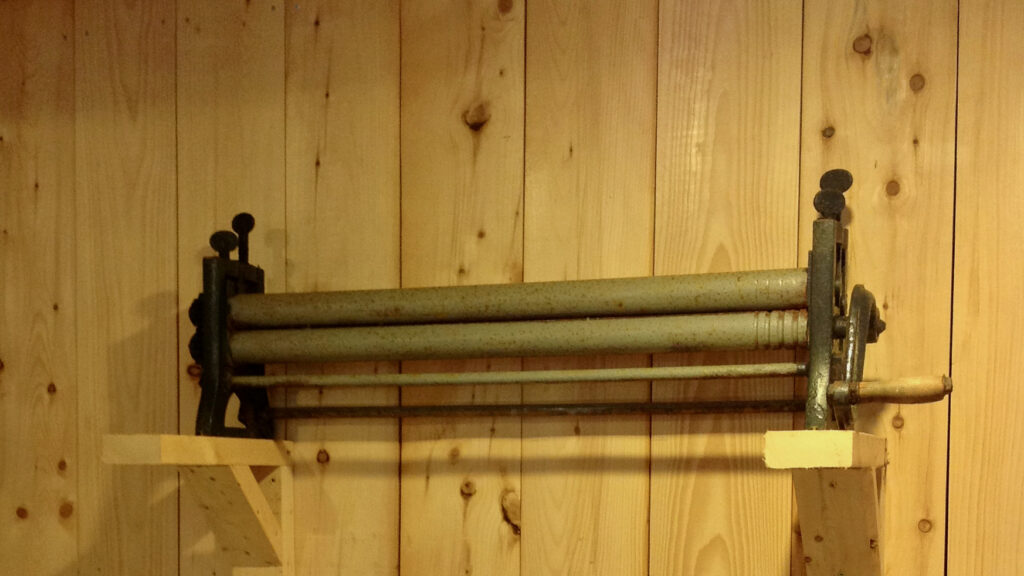

Item One is a lobster tray and it came to mind when I saw this advertisement in the April 25, 1923 Guardian.

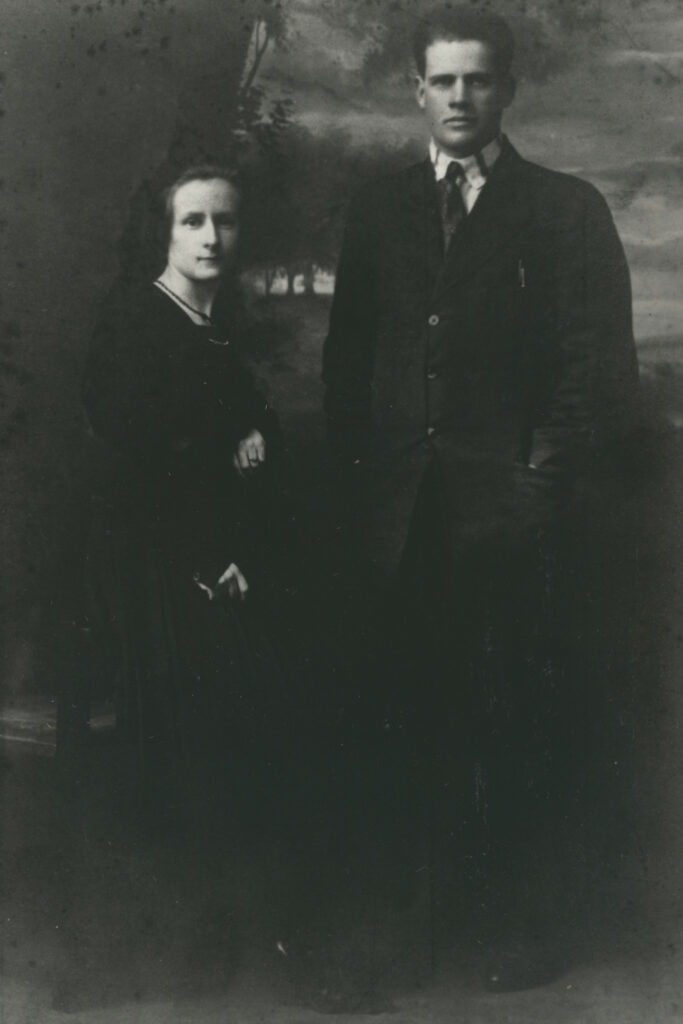

My great grandparents, Eva and Ernest Hardy, ran a lobster canning factory on the Conway Sandhills at Hardy’s Channel off Milligan’s Wharf, PEI from 1901 until Ernest’s death in 1946. My mother spent her childhood summers at the factory, so I have her stories and even a few photos of the place, but not much of the physical elements of that bustling enterprise remain.

Some of the buildings now at Milligan’s Wharf made up part of the factory and were hauled over to the mainland of PEI in the early 1960s to be used by my mother’s uncles. Some were later repurposed for cottages, one into a snack bar, and one sadly sits abandoned by next-generation owners who have little regard for its history.

The factory equipment – boilers, tools, tables, canners, utensils – are probably all long gone, no doubt sold to others in the same business or repurposed by the family, which is why I was surprised to come across the tray in our shop building some years ago.

I’m not sure why we have the tray, though I expect it came from one of the buildings on the home property once owned by Ernest and Eva and later occupied by their son, Elmer. My mother helped Elmer in his market garden and he would often give her old things that were hanging around the place and probably in his way. She had a collectors spirit, for which I am thankful.

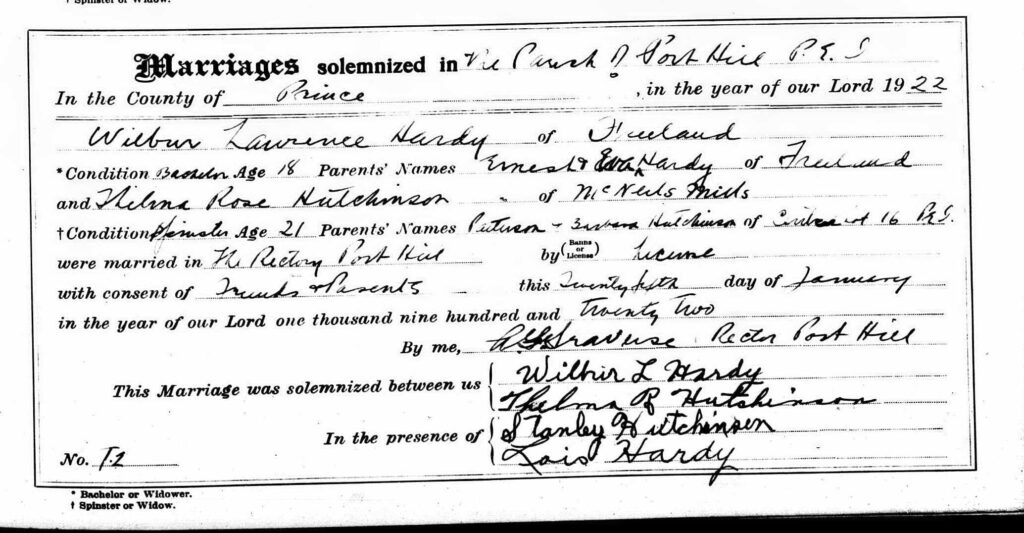

Until I saw Fred H. Trainor’s advertisement, I had assumed the tray had been made by someone working for Ernest, and that could still be true. Fishermen built their own lobster traps and boats, so making some rough trays wouldn’t be a big deal. My mother’s father, Wilbur Hardy, was not a fisherman but did have a small box mill that he used to make lathes and boards for crates, so he would have been well positioned to fashion the wood for a tray for his father’s business.

The tray is base is galvanized metal. The wooden frame is 13.5 inches wides, 26.25 inches long and 2.25 inches deep. There are small pieces of wood, tapered by rough carving on either end, on the bottom on the two shorter sides that would allow the tray to sit slightly off of a table for drainage. The drainage holes are evenly spaced 1.5 inches apart, faint grid lines directing the precise location for punching. Considering the amount of salt that would have been around the factory, it’s miraculous the nails holding the frame together are still able (barely) to do their work of holding the pieces together.

The factory was probably a difficult place to work in a challenging location: a sandbar on the north shore of PEI. There was never electricity there, though they did get a gasoline-powered stationary engine in the late 1920s, which was later rescued from a barn by my cousin. He thinks it was used to run a saw to cut up firewood, which was needed in large amounts to fire the boilers that produced hot water and steam for the factory.

Everything was done by hand, in conditions that would probably not be considered sanitary today. The boiler man drew water from a hand-dug well using a bucket and would fill the huge boiler that produced steam to cook the lobsters, keeping a hot wood fire roaring all day. Workers, both men and women, would open the cooked lobsters, first ripping off the claws and cracking them at the knuckle with large knives to extract the meat, pulling out the tail meat, and ripping the bodies apart.

The little legs were fed through the wringer that came off a washing machine, squeezing the sweet meat out of them. My mother says this was the only job she ever did in the factory. The leg meat was added to the tomalley (“the green stuff” inside a lobster body) and roe to make lobster paste, also canned and sold. They also canned mackerel.

Leftover lobster bodies quickly become smelly, and piles of them would attract flies and wild creatures, so my mother says they were dumped back into the ocean by the fishermen or hauled to farms to be used as fertilizer. One of her uncles would fill his dory with bodies, take them back to the mainland, throw them into a wagon, and spread them on his farm fields to be disced under. They would certainly be scavenged by animals and birds when fresh, but eventually they would break down and act as a good fertilizer, or as good as a fertilizer could be before chemicals fertilizers were created. Even with all that effort of spreading lobster bodies, that uncle called his place Wild Rose Farm because that’s all the land was good for growing!

One of the canning machines, a greasy looking hand-cranked device, was in Elmer’s shop building. He raised chickens for eggs and meat, and canned chicken, beef and some fish well into the 1980s. Some people in our area still can beef, chicken and bar clams, though use glass canning jars and not the more tricky metal cans.

My mother says her grandmother, Eva, packed every can as she had “the knack”, and probably also wanted to make sure the weight was exact. A piece of white parchment paper was placed in the bottom of the flat, wide cans, and she would carefully fit tails, claws and bits of meat to bring it up to the correct weight. Once the cans dried and cooled after processing, a label would be affixed with glue or paste. My mother says her grandparents’ product was sold to wholesalers, so there was not an E.A. Hardy brand, but more likely they were canned for DeBlois Brothers wholesalers in Charlottetown, or maybe the large PEI retailer, Holmans.

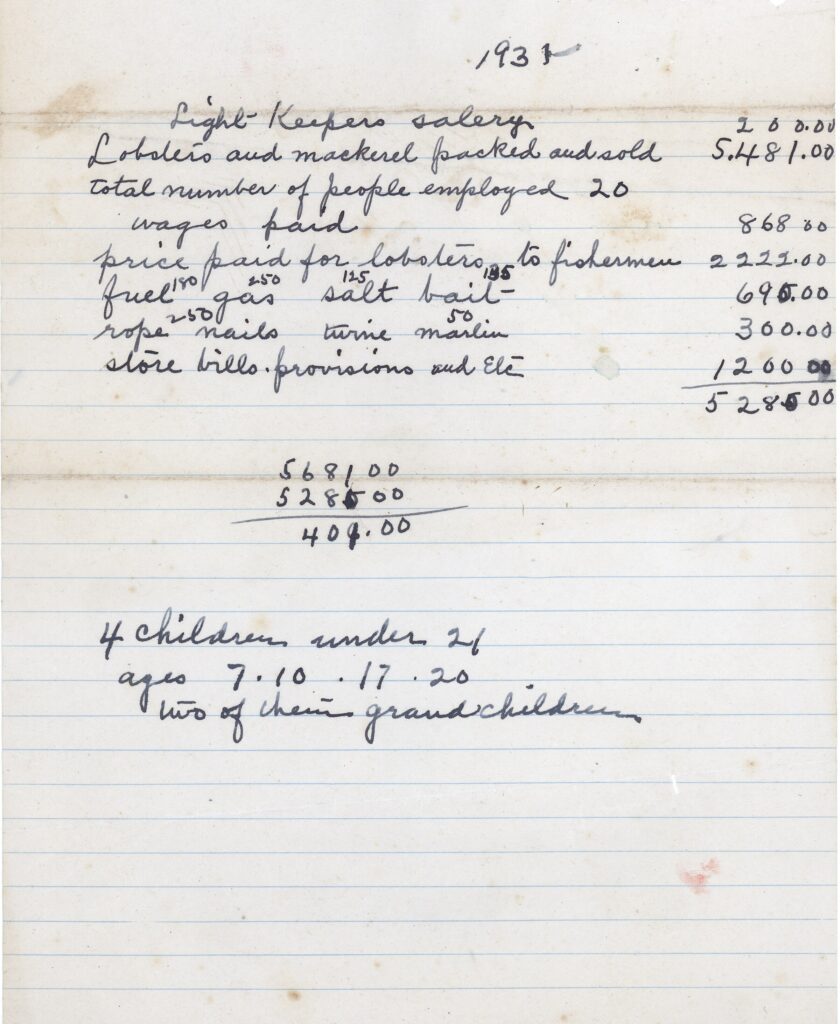

My great grandmother likely handled the tray thousands of times over the 45 years they worked each summers to make the money that would carry them over the rest of the year. “Factory owner” makes it sound like they were rich, and they definitely were not. They had a telephone, but no electricity and never had a car or truck. The furthest from PEI either of them ever got, that I know of, was when when my great grandfather went to Montreal for an operation, but I don’t think my great grandmother ever left PEI, or even went to Charlottetown! I gather they were well-respected in the community as being industrious and honest, but they had little more than anyone else.

I think of the countless people who held that tray, working long hours to make a product they probably couldn’t afford to buy. That’s still the story for millions today who produce our clothing, electronics and food in hidden corners of the world. They make little, the corporations make a lot, and we get cheap things.

There are still lobster processing factories on PEI, some of it being canned but most of it frozen. Local workers became more difficult to find over time, so a large percentage of factory workers now come from places like the Philippines. Those temporary foreign workers have supported the lobster fishing industry in a way that is perhaps not acknowledged often enough, as the market for fresh lobster is limited and processing the only way to ensure there is a bigger market.

Lobster fishing and processing is still difficult, even dangerous, work. Thank the lobster, thank the fisher, thank the factory worker who holds the tray.